|

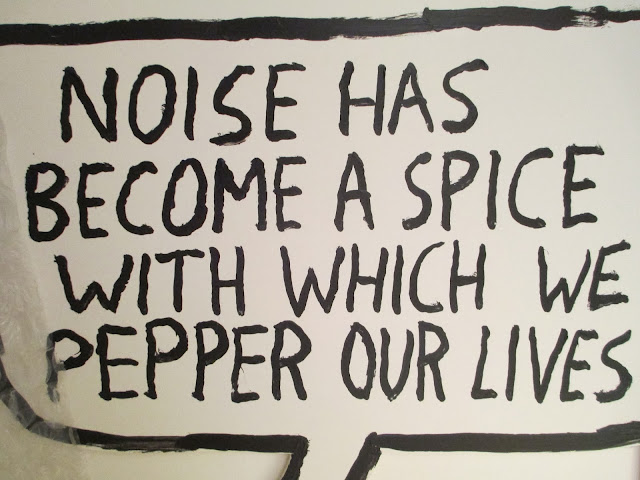

Austin's been making such fresh and exciting paintings!!! I was so inspired and blown away by visiting his studio.

|

|

This incredible gem is going to be in the pink show that I am putting together at Cathouse FUNeral!! Our opening will be January 18.

|

|

Close-up of the crowd. The painting also has a biographical aspect, since Austin was a boxer in the past.

|

|

The tears have such a compelling and tangible, physical presence, that they act as a barrier separating the viewer from the helpless woman. It calls to mind all those portraits that Picasso painted of Dora Maar crying. When Kippenberger learned that he was dying, he painted a series of Picasso's women crying over his own death. People were surprised by how beautifully and skillfully Kippenberger had painted this last series, few people knew that he was capable of such technical excellence. Beauty and technical facility was something that Kippenberger was deeply suspicious of his entire life, because he was more interested in expressing something more human and honest. Nietzsche writes about how virtuosity and a mastery of technique are a disguise that artists use to hide beneath. Anyone can become a skilled technician; it's much harder to become an artist.

Link |